The term taweez refers to a written amulet or inscribed prayer used across many Muslim societies, with variations in language and religious interpretation. While taweez can be created for protection, healing, or blessing, the category of the love taweez occupies a distinct position in South Asian and Middle Eastern vernacular religious practice. Unlike protective or power-focused amulets, a love taweez is typically associated with emotional stability, romantic commitment, or gaining familial approval in matters of marriage.

Anthropologically, taweez belongs to the domain of embodied and everyday religiosity. It aligns with Saba Mahmood’s concept of “lived religion” where devotional practices are integrated into daily moral life, and with Birgit Meyer’s framework of “material religion” which emphasizes the agency of objects, scripts, and sensory forms in shaping belief. Taweez also reflects the dynamics of “Transnational Islam” described by John Bowen, as it travels with migrants and adapts to new cultural settings.

Historical and Regional Background

The practice of crafting taweez has deep historical roots across multiple Islamic regions, developing distinct local forms while maintaining a shared conceptual basis: written prayers or Qur’anic verses enclosed within a protective container. In South Asia, taweez traditions became especially prominent from the Mughal period onward, supported by Persian court culture and later by rural Sufi networks. Scholars such as Bruce Lawrence and Barbara Metcalf have documented the widespread use of amulets in North India and Pakistan, where terms like “mohabbat ka taweez” emerged to describe amulets specifically oriented toward matters of affection, attraction, or marriage harmony.

In Afghan and Pashtun regions, anthropological work by Thomas Barfield and others notes the use of written charms for both protection and interpersonal reconciliation. Although Afghan taweez practices often prioritize protection and healing, love-related amulets appear within household-level ritual repertoires, especially in Pashto-speaking communities where traditional healers (mullah, tabib) provide written charms for emotional or marital tensions.

In the Middle East, the distinction between taweez, ruqyah, and hirz is more pronounced. Amulets may derive from classical Arabic manuscripts or Sufi devotional texts, and they are less commonly associated with “love” as an explicit category. Nonetheless, the broader tradition of inscribed protective objects—documented in studies of Ottoman, Yemeni, and Egyptian folk practices—provides a historical backbone for the taweez used globally today.

Across these regions, Sufi orders such as the Chishti, Qadiri, and Naqshbandi contributed to the diffusion of taweez-making techniques, emphasizing scripted blessings, geometric designs, and specific Qur’anic passages. This layered history forms the foundation upon which contemporary “love taweez” practices evolve, especially as they travel with migrants to new cultural environments.

Migration to the United States and the Preservation of Ritual Practices

Muslim migration to the United States has accelerated since the late twentieth century, shaped by family reunification policies, professional visa programs, and refugee resettlement. Pew Research Center data identifies South Asians, Middle Easterners, and East Africans as some of the fastest-growing Muslim populations in the country. These communities brought with them not only religious beliefs but also a broad repertoire of ritual-material practices, including the use of taweez.

Unlike formal Islamic education, taweez knowledge typically travels through families, neighborhood healers, and Sufi lineages rather than through institutional structures. As migrants settled in urban hubs such as Houston, Chicago, Detroit, Queens, and Northern Virginia, they recreated familiar networks of religious specialists (amil, pir, baba) who continued writing amulets and advising on relational or marital concerns. In many cases, these specialists were not trained clerics but individuals recognized within their home communities for expertise in scriptural inscriptions, medicinal verses, or spiritual counseling.

The American environment introduces both constraints and adaptations. Limited availability of local healers pushes many migrants to request taweez from relatives abroad or from amils who operate through phone calls, messaging apps, or mailed packages. Younger migrants, especially students and recent arrivals, often rely on transnational ties to obtain amulets, bypassing local mosques where the practice may be discouraged by imams aligned with stricter theological interpretations.

Thus, taweez persists not merely as a remnant of “old-world” custom but as a flexible ritual technology that continues to meet emotional and relational needs within the diasporic setting. These dynamics set the stage for the specific role played by love taweez in U.S. Muslim communities.

The Social Function of Love Taweez in American Muslim Communities

Within U.S. Muslim migrant communities, love taweez frequently operate as tools for negotiating emotional, familial, and cultural pressures surrounding romantic relationships. South Asian and Middle Eastern migrants encounter a landscape in which American norms of dating, autonomy, and partner choice often conflict with expectations rooted in their countries of origin. This clash is evident in ethnographic studies such as Karen Leonard’s work on South Asian Muslims in California, which describes recurring tensions between individual romantic preferences and family-centered decision-making.

Among first-generation migrants, love taweez often address issues that cannot be openly discussed: fear of parental disapproval, anxiety about “improper” relationships, or uncertainty about partners met in U.S. academic or professional settings. For second-generation youth, raised within American social environments yet accountable to cultural expectations, a love taweez can function as a discreet method of emotionally managing the uncertainty of cross-cultural relationships. It allows them to pursue personal commitments while maintaining a symbolic connection to community norms.

Differences emerge across ethnic groups. Among Bangladeshi Americans, research by Nazli Kibria shows that marriage is often framed as a family-managed project, which enhances the appeal of ritual interventions when disputes arise. Pakistani and Indian migrants commonly use love taweez to stabilize relationships facing disapproval or geographic separation. Within Afghan and Pashtun communities, taweez more often address marital harmony than dating, reflecting social discouragement of premarital relationships. Somali diaspora households sometimes incorporate hirzi-style amulets to address emotional strain within marriages, though practices vary widely.

Because love and courtship are sensitive topics in many Muslim families, the love taweez often becomes a quiet emotional technology, used privately to manage hope, anxiety, and relational instability. Its role is less about “influencing” others and more about providing a culturally meaningful sense of agency within complex social structures.

Materiality and Production Techniques

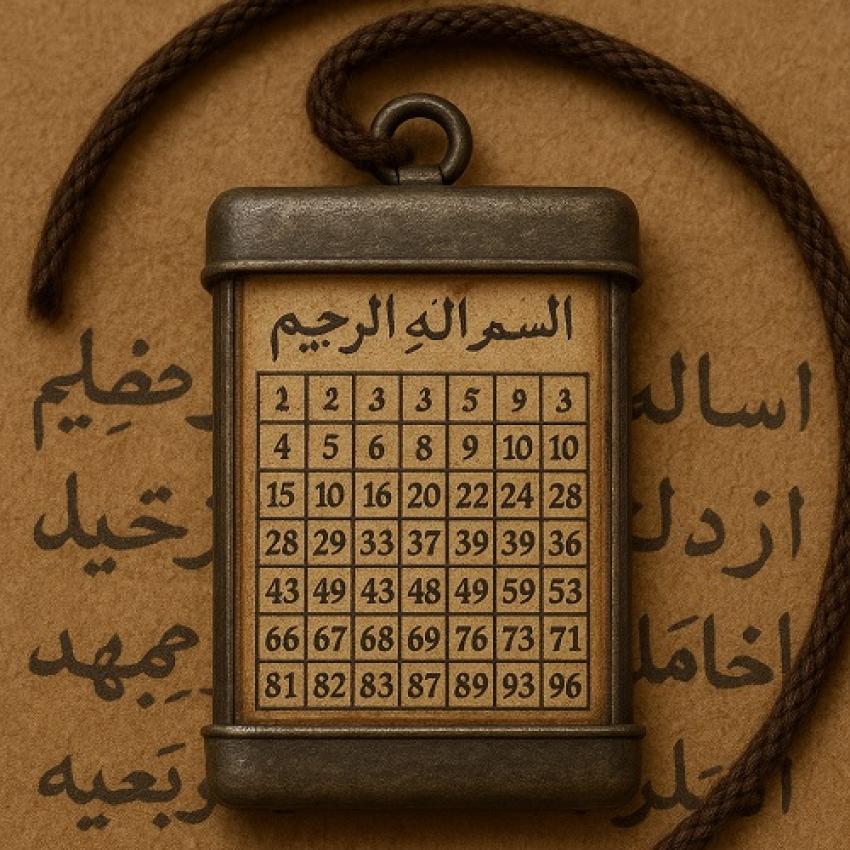

Love taweez are defined not only by intention but by their material construction, which follows established regional conventions adapted to available resources in the United States. Traditionally, taweez are produced on hand-cut paper using black or occasionally saffron-based ink. The completed script is folded into compact geometric shapes and placed in a leather pouch, metal capsule, or cotton cloth that can be worn discreetly around the neck, wrist, or waist. In the U.S. context, migrants often replace traditional materials with readily available alternatives such as synthetic thread, machine-stitched pouches, or aluminum cases purchased online.

The calligraphy is central. In South Asian love taweez, healers frequently write verses associated with emotional bonding or divine compassion. The most commonly referenced passage is Surah Yusuf, particularly ayahs linked to patience, longing, and relational integrity; this association is well documented in Urdu devotional literature. Some taweez include short supplications (duas) phrased in Urdu or Arabic, written in compact scripts designed to remain unread once folded.

Two dominant forms appear across communities: naqshi taweez, which use symbolic grids, numeric squares, and geometric diagrams; and ruhani taweez, which rely solely on textual prayers without diagrams. Naqshi forms are more prevalent among South Asian healers, while ruhani forms appear across multiple regions.

Online Taweez Services and Digital Transformation

The expansion of digital communication has significantly reshaped how U.S. Muslim migrants access and interpret love taweez. Instead of relying solely on community-based healers, many now consult online amils, most of whom operate from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and parts of the Middle East. These practitioners advertise through WhatsApp, Facebook pages, Instagram profiles, and YouTube channels, offering services that were once strictly local. The shift is particularly visible among students and recent migrants, who use digital platforms to maintain religious and cultural ties with specialists from their home regions.

Google Trends data shows recurring spikes in U.S. searches for terms such as “taweez for love” “mohabbat ka taweez” “love amulet Islam” and similar Urdu/Hindi phrases. These patterns correspond with increased visibility of online spiritual service providers targeting diaspora audiences. Clients typically receive scanned scripts, voice-note instructions, or recorded prayers, which they then reproduce manually using local materials. This model reflects a transnational religious economy, where spiritual authority flows across borders without physical presence.

However, digitalization introduces new risks. South Asian diaspora forums and Reddit threads frequently discuss fraudulent online amils, reporting exaggerated claims, high fees, or emotionally manipulative tactics. Some users describe paying for amulets that never arrive or receiving generic PDFs unrelated to their stated concerns. These narratives shape community perceptions, prompting skepticism even among those who value traditional practices.

At the same time, digital platforms decentralize authority. Local imams in U.S. mosques—many of whom discourage taweez—cannot control the influence of remote spiritual specialists who speak the same language and understand the cultural context. This weakening of local religious authority reinforces migrants’ reliance on online networks, creating a hybrid model in which taweez practices adapt to the realities of global connectivity.

Religious Debates: Legitimacy and Controversy

The use of love taweez in U.S. Muslim communities exists within a landscape of active theological disagreement. Much of the controversy stems from divergent interpretations within global Islam, which migrants carry with them into the American religious environment. Among the most vocal critics are scholars influenced by Salafi interpretations. Institutions such as Islam Q&A—a widely referenced Salafi fatwa platform—publish rulings declaring most amulet practices impermissible, arguing that writing unknown symbols or relying on objects for spiritual benefit could constitute shirk or unwarranted innovation. These rulings circulate frequently in U.S. daʿwah groups, shaping attitudes among American-born Muslims and converts.

In contrast, Deobandi authorities—such as Darul Uloom Karachi and Darul Ifta India—maintain a more conditional stance. Their fatwas distinguish between amulets containing Qur’anic verses (permissible under strict conditions of clarity and monotheism) and those containing numerological grids or unknown symbols (discouraged). This nuance reflects South Asian scholarly traditions, where taweez have long been integrated into everyday piety. Migrants from Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh often draw on these teachings to justify their continued use of love taweez.

Sufi-oriented communities add a third strand, emphasizing the historical continuity of amulet practices within Chishti, Qadiri, and Naqshbandi lineages. For them, taweez function as extensions of prayer, not substitutes for divine will. In U.S. Sufi circles, taweez are typically framed as devotional aids rather than supernatural tools.

Conclusion

The use of love taweez among Muslim migrants in the United States illustrates how religious-material traditions adapt when carried across borders. Rather than fading in a secular, institutionally fragmented environment, taweez practices evolve into flexible emotional and cultural technologies that help individuals navigate relational uncertainty, family expectations, and the psychological stresses of migration. Their persistence reflects the broader dynamics of transnational Islam, where ritual knowledge circulates through extended kinship networks, digital platforms, and spiritual specialists operating across continents.

Ultimately, the love taweez remains significant not as a magical instrument but as a material expression of hope, a means through which migrants manage the complexities of intimacy and identity in a new cultural landscape. Its continued use underscores how deeply personal and relational needs intersect with inherited ritual forms, sustaining practices that bridge continents, generations, and emotional worlds.